How does a File System Work?

You're aware of what files are. You've also heard about different file systems. But how do they work?

You’re probably aware of files as a “stream” of bytes that can be read and written to. You’re also aware that files are stored in a secondary storage like a hard disk or SSD. You’ve most likely also heard about different file systems like FAT, NTFS, ext4, etc. But there are still some questions that need answering.

Storing a file

Although it feels like files are stored in contiguous memory because of the programming interface that the OS provides, it is (almost) never the case. It’s easy to see some of the problems in this approach.

- You would have to specify the size of the file at the time of creation so that the OS can know how much memory to allocate.

- Once you decide to add more content to the file, you would need to relocate the whole file to a bigger block of memory.

- Managing the holes in the memory due to file updates and deletions would be a nightmare and it would lead to inefficient memory usage.

This is not to say that this approach is useless. It provides much value for the cases where file size is known in advance (read-only CDs anyone?). But it does no good for a read-write system like a hard disk. Then what scheme do they use?

Most file systems think of files as blocks of bytes. e.g. a 12 MB file can be thought of as a sequence of 12 * 1024 blocks of size 1 KB each. The blocks can be present anywhere in the storage; we just need a way to know the correct order.

Order of the blocks

Now, we just need a way to store this list. And when you have a variable sized, ordered list of things, the first thing that comes to mind is a linked list.

With a linked list, each block in the file can reserve some space to store the address of the next block in the file. To read the whole file, it is sufficient to know the address of the first block.

The problem of random access

This approach works well if all we care about is sequential reads and writes. But what about random access? You would need to read each block in primary memory to get the address of the next block.

The problem of block sizes

Even if you do not care about random access, there’s still the question of peculiar box sizes. In the majority of cases, reads and writes are in powers of 2. If your block of size 1 KB has to store the address of the next block, it needs to reserve some space which change the size of available space from 1 KB to 1 KB - 2n. *visible cringe*

These problems can be solved in two ways.

1. File Allocation Table

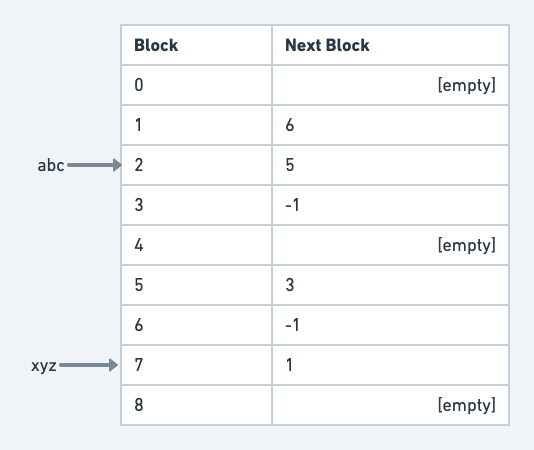

If you have a table to map each block to the next block, that’s enough! This table, called File Allocation Table, would be a map of all the blocks in the disk.

Consider the table in the figure below. The file abc starts from block 2. The next block in the list is 5. The next block after 5 is 3. And since 3 has -1 as the next block, it is the last block.

If the user now wants to write some more content into the file, we just add another block and put its address in the “next block” of 3.

A small File Allocation Table

With this, we’ve solved the problem of random access, because we just have to load the FAT instead of loading each block in memory; we can even cache it. And we’ve also solved the problem of odd file sizes because we no longer have to reserve space for addresses of next block.

The only problem with this approach is keeping the table in memory. As the disk size grows, the table grows proportionately.

2. Index nodes (i-nodes)

Instead of keeping the whole table in memory, we can just keep a table specific to a single file and load this table into memory when loading the file. This “table” is called the i-node.

Along with the information on blocks, it can also store some more metadata about the file so that everything is in one place. This i-node is equivalent to the whole file minus the contents (which are present in blocks). It can store information about directory structures, number of references, and so on.

If the number of blocks in the file is greater than what can fit into 1 i-node, you can point it to another i-node which stores info about more blocks.

What about directories?

Directories are just another type of files. They have i-nodes similar to those of files with similar metadata. The directory points to the i-nodes of other files which are present in it.

In Unix-like systems, there’re two special entries in a directory i-node:

. – which points to the directory itself.

.. – which points to the parent of the directory.

Each file system also has a “root” directory whose i-node address is stored in a known location. It is file system specific e.g. it can be the first i-node in some file system or in some other, it could be some random i-node but with it’s address stored in the first block, etc.

There’s much much more to file systems. People have written whole books on them. This post was just about how the most basic file systems work. There is still more to cover like shared files, maintaining consistency in file systems, security, caching, etc. There’re also numerous file systems which are completely different from the one I just wrote about (e.g. lfs).

I’m yet to implement a file system for Jazz, which is an OS I’m writing, so no implementation details yet. Let’s see how that goes.